Scientists have discovered a rare gravitationally lensed supernova, “SN Zwicky,” which provides unique insights into galaxy cores, dark matter, and the mechanics of universe expansion. This discovery utilizes gravitational lensing, a phenomenon that magnifies celestial objects, according to Einstein’s theory of relativity.

Researchers gain insight into how the universe is expanding thanks to gravitational lensing, a natural phenomenon that warps space around galaxies and visually magnifies celestial objects.

According to Einstein’s general theory of relativity, time and space are fused together in a quantity known as spacetime. The theory suggests that massive objects, like a galaxy or galaxy clusters, can cause spacetime to curve. Gravitational lensing is a rare yet observable example of Einstein’s theory in action; the mass of a large celestial body can significantly bend light as it travels through spacetime, much like a magnifying lens. When light from a more distant light source passes by this lens, scientists can use the resulting visual distortions to view objects that would otherwise be too far away and too faint to be seen.

An international team of scientists, including University of Maryland astronomer Igor Andreoni, recently discovered an exceptionally rare gravitationally lensed supernova, which the team named “SN Zwicky.” Located more than 4 billion light years away, the supernova was magnified nearly 25 times by a foreground galaxy acting as a lens. The discovery presents a unique opportunity for astronomers to learn more about the inner cores of galaxies, dark matter, and the mechanics behind universe expansion. The researchers published their findings—including a comprehensive analysis, spectroscopic data, and imaging of SN Zwicky—in the journal Nature Astronomy on June 12, 2023.

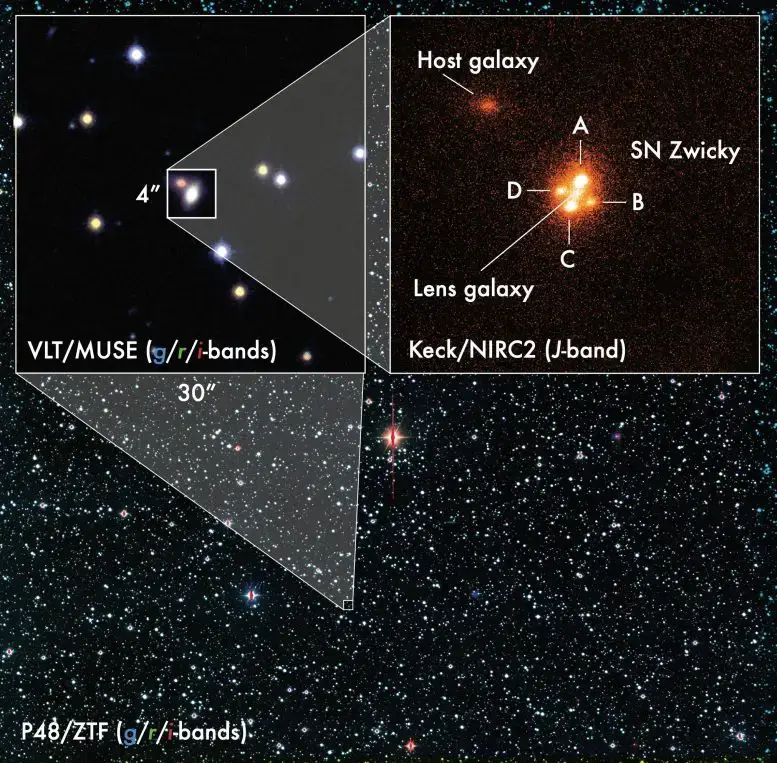

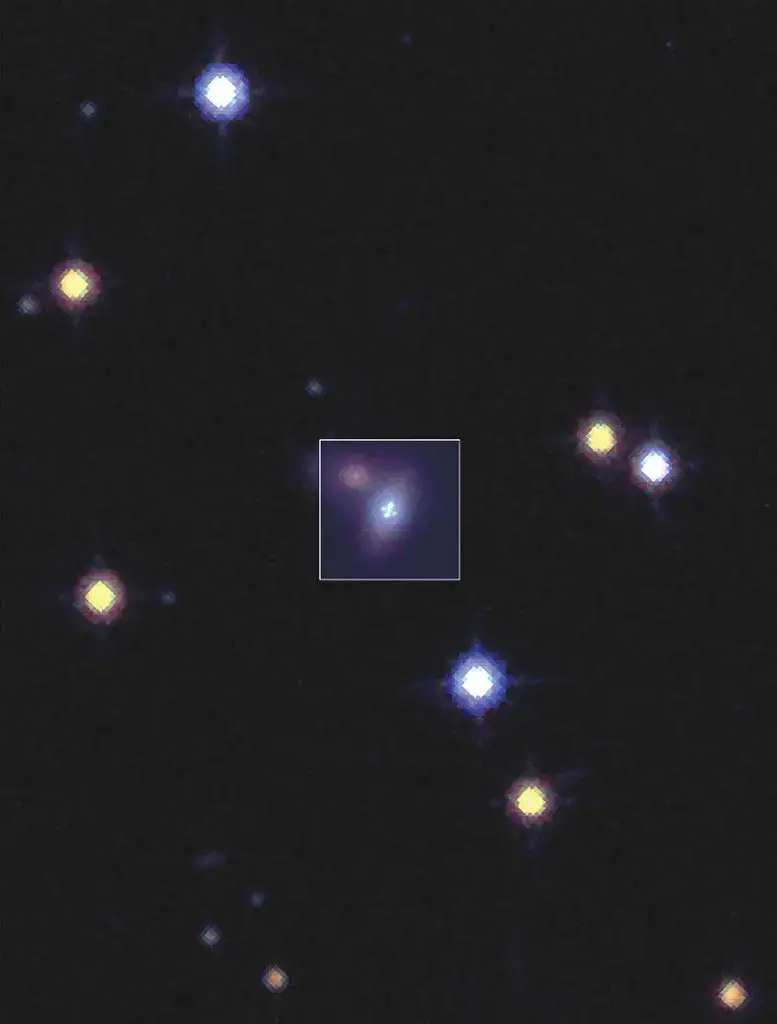

Zooming in to supernova Zwicky: starting from a small portion of the Palomar ZTF camera, one out of 64 “quadrants”, each one containing tens of thousands of stars and galaxies, the zoom-in takes us to detailed explorations carried out with the larger and sharper VLT and Keck telescopes in Chile and Hawai’i respectively. On the best resolved Keck images, the four nearly identical “copies” of supernova Zwicky can be seen. The multiple images arise due to the warping of space caused by a foreground galaxy, also seen in the center and approximately halfway between the site of the supernova explosion and Earth. Credit: J. Johansson

“The discovery of SN Zwicky not only showcases the remarkable capabilities of modern astronomical instruments but also represents a significant step forward in our quest to understand the fundamental forces shaping our universe,” said the paper’s lead author Ariel Goobar, who is also the director of the Oskar Klein Center at Stockholm University.

Initially detected at the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF), SN Zwicky was quickly flagged as an object of interest due to its unusual brightness. Then, using adaptive optics instruments on the W.M. Keck Observatory, the Very Large Telescopes, and NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, the team observed four images of SN Zwicky taken from different positions in the sky and confirmed that gravitational lensing was behind the supernova’s extraordinary radiance.

SN Zwicky. Credit: Joel Johansson, Stockholm University

According to Andreoni, who is a postdoctoral associate in UMD’s Department of Astronomy and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, supernovae like SN Zwicky play a crucial role in helping scientists measure cosmic distances.

“SN Zwicky not only is magnified by the gravitational lense, but it also belongs to a class of supernovae that we call ‘standard candles’ because we can use their well-known luminosities to determine distance in space,” Andreoni explained. “When a source of light is farther away, the light is dimmer—just like seeing candles in a dark room. We can compare two light sources in this way and gain an independent measure of distance without having to actually study the galaxy itself.”

In addition to being useful as a metric for cosmic distance, SN Zwicky also opens new avenues of research for scientists exploring the properties of galaxies, including dark matter (which is matter that does not absorb, reflect or emit light but make up the majority of matter in the universe). Researchers also believe that lensed supernovae like SN Zwicky could prove to be very promising tools for examining dark energy (a mysterious force counteracting gravity and drives the accelerated expansion of the universe) and refining current models describing the universe’s expansion, including the calculation of the Hubble constant—a value that describes how fast the universe is expanding.

For Andreoni, who is preparing for the opening of the Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile, the team’s success in identifying and analyzing SN Zwicky is only the beginning. Now still in its construction phase, the new observatory is expected to begin full operations in 2024 and build upon the team’s findings as it takes multiple images of the entire visible sky to search for other supernovae and asteroids. Andreoni believes that the “big picture” tactic used to find SN Zwicky will continue to help scientists gather large volumes of data about celestial events in the sky.

“This discovery paves the way to find more of such rare lensed supernovae in future big surveys that will help us study transient astronomical events like supernovae and gamma ray bursts,” Andreoni said. “We look forward to more unexpected discoveries using broad, untargeted optical surveys of the sky like the one that helped us identify SN Zwicky. With this approach, we’ll be able to probe the transient sky with an unprecedented depth.”

To learn more about how gravitational lensing works, please view the short animation below:

Objects with large masses such as galaxies or clusters of galaxies warp the spacetime surrounding them in such a way that they can create multiple images of background objects. This effect is called strong gravitational lensing. Credit: ESA/Hubble, NASA

The paper, “Uncovering a population of gravitational lens galaxies with magnified standard candle SN Zwicky,” was published on June 12, 2023, in Nature Astronomy.

Reference: “Uncovering a population of gravitational lens galaxies with magnified standard candle SN Zwicky” by Ariel Goobar, Joel Johansson, Steve Schulze, Nikki Arendse, Ana Sagués Carracedo, Suhail Dhawan, Edvard Mörtsell, Christoffer Fremling, Lin Yan, Daniel Perley, Jesper Sollerman, Rémy Joseph, K-Ryan Hinds, William Meynardie, Igor Andreoni, Eric Bellm, Josh Bloom, Thomas E. Collett, Andrew Drake, Matthew Graham, Mansi Kasliwal, Shri R. Kulkarni, Cameron Lemon, Adam A. Miller, James D. Neill, Jakob Nordin, Justin Pierel, Johan Richard, Reed Riddle, Mickael Rigault, Ben Rusholme, Yashvi Sharma, Robert Stein, Gabrielle Stewart, Alice Townsend, Yozsef Vinko, J. Craig Wheeler and Avery Wold, 12 June 2023, Nature Astronomy.DOI: 10.1038/s41550-023-01981-3

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant Nos. AST-2034437 and 1106171), the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (under Dnr KAW 2018.0067 and research project grant “Understanding the Dynamic Universe”), the Swedish Research Council (Project No. 2016-06012, and Contract Nos. 2020-03444 and 2020-03384), the European Research Council (Grant No. 759194-USNAC), the European Organization for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere, and the United Kingdom Science and Technology Facilities Council. This story does not necessarily reflect the views of these organizations.