They have now carbon-dated the jaw bone to confirm the man probably lived in the 6th century BC. An examination of the teeth and skull revealed he was between 26 and 45 years old when he died.

It appears that he was first hit hard on the neck, which was then severed with a small sharp knife, according to marks on the vertebrae, but experts can only guess why the man died such a violent death.

There has previously been a suggestion that he was hanged, but experts have largely ruled out his head being used as a trophy – which was a grim practice in Iron Age societies – because there are no signs of preservation or smoking.

Speaking two years ago, Sonia O’Connor, research fellow in archaeological sciences at the University of Bradford, said: ‘The hydrated state of the brain and the lack of evidence for putrefaction suggests that burial, in the fine-grained, anoxic sediments of the pit, occurred very rapidly after death.

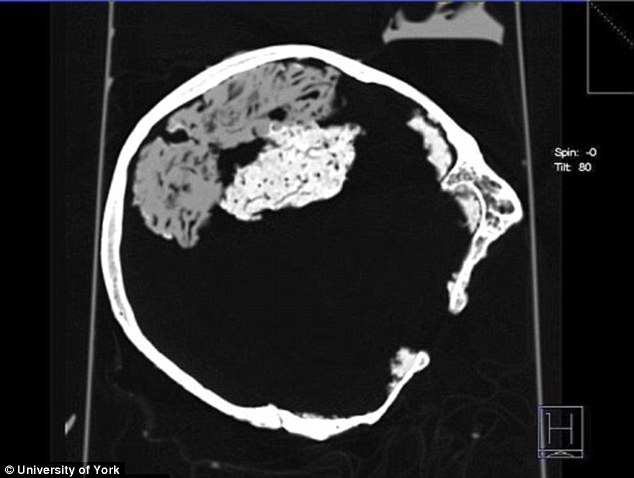

Scientists said there was no trace on the brain of the usual preservation methods such as embalming or smoking. This x-ray shows the position of the shrunken brain inside the skull

Scientists said there was no trace on the brain of the usual preservation methods such as embalming or smoking. This x-ray shows the position of the shrunken brain inside the skull Speaking two years ago, Sonia O’Connor, research fellow in archaeological sciences at the University of Bradford, said: ‘The hydrated state of the brain (pictured) and the lack of evidence for putrefaction suggests that burial, in the fine-grained, anoxic sediments of the pit, occurred very rapidly after death’

Speaking two years ago, Sonia O’Connor, research fellow in archaeological sciences at the University of Bradford, said: ‘The hydrated state of the brain (pictured) and the lack of evidence for putrefaction suggests that burial, in the fine-grained, anoxic sediments of the pit, occurred very rapidly after death’

‘This is a distinctive and unusual sequence of events, and could be taken as an explanation for the exceptional brain preservation.’

However, the larger mystery is how his brain was preserved naturally, when bodies buried in the ground typically rot because of a mixture of water, oxygen, as well as a temperature allowing bacteria to thrive.

When one or more of these factors is missing, preservation can occur. In the case of the Heslington Brain, the outside of the head rotted as normal, but the inside was preserved. Experts believe the head was cut from the man’s body almost immediately after he was 𝓀𝒾𝓁𝓁ed and buried in a pit dug in wet clay-rich ground.

This environment provided sealed, oxygen-free burial conditions.

In 2009, archaeologists from York Archaeological Trust uncovered the skull with the jaw and two vertebrae still attached to it, in Heslington, York, (marked on this map)

In 2009, archaeologists from York Archaeological Trust uncovered the skull with the jaw and two vertebrae still attached to it, in Heslington, York, (marked on this map) The skull was found face-down in a pit without any evidence of what had happened to the rest of the body. This image shows archaeologists sifting through the muddy pit at the site near the University of York where the brain was found

The skull was found face-down in a pit without any evidence of what had happened to the rest of the body. This image shows archaeologists sifting through the muddy pit at the site near the University of York where the brain was found

While over time, the skin, hair, and flesh of the skull rotted away, the fats and proteins of the brain tissue linked together to form a mass of large complex molecules.

This resulted in the brain shrinking, but it also preserved its shape and many microscopic features only found in brain tissue, they explained.

As there was no new oxygen in the brain and no movement, it was protected and preserved, allowing scientists to study it today.

Speaking two years ago, Sonia O’Connor, research fellow in archaeological sciences at the University of Bradford, said: ‘It is rare to be able to suggest the cause of death for skeletonised human remains of archaeological origin.

‘The preservation of the brain in otherwise skeletonised remains is even more astonishing but not unique.

‘This is the most thorough investigation ever undertaken of a brain found in a buried skeleton and has allowed us to begin to really understand why a brain can survive thousands of years after all the other soft tissues have decayed.’