For the Smithsonian’s Sidedoor podcast, host Haleema Shah tells the story of an unapologetically gay African-American performer in 1920s and 30s.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e8/10/e810d384-5022-4ddb-85b1-874effa7b4de/2013_46_25_15_001.jpg)

In 1934, a midtown Manhattan nightclub called King’s Terrace was padlocked by the police after an observer complained of the “dirty songs” performed there.

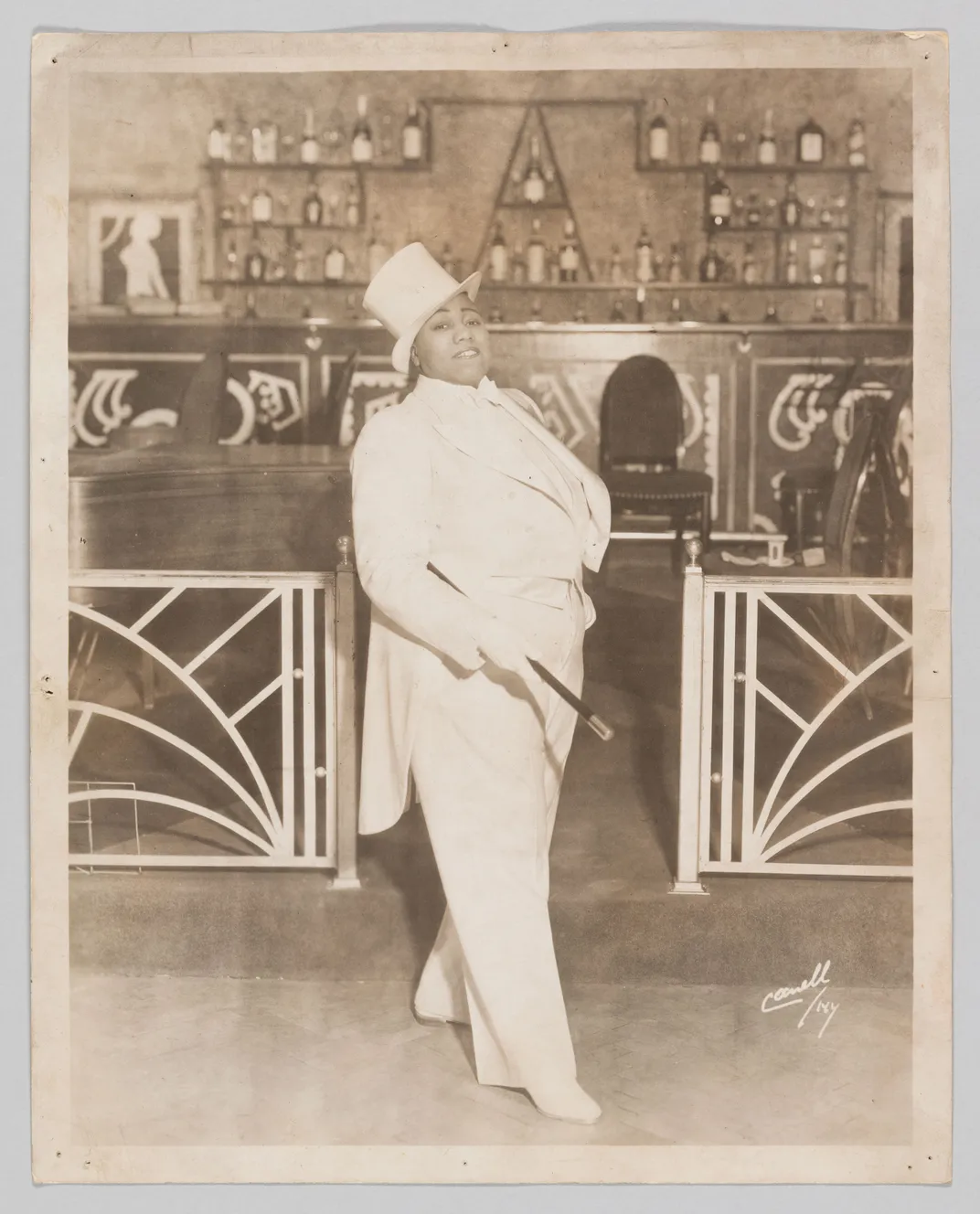

The after-theater club near Broadway was where a troupe of “liberally painted male sepians with effeminate voices and gestures” performed behind entertainer Gladys Bentley, who was no less provocative for early 20th-century America. Performing in a signature white top hat, tuxedo and tails, Bentley sang raunchy songs laced with double-entendres that thrilled and scandalized her audiences.

And while the performance of what an observer called a “masculine garbed smut-singing entertainer” led to the shutdown of King’s Terrace, Bentley’s powerful voice, fiery energy on the piano and bold lyrics still made her a star of New York City nightclubs.

Her name doesn’t have the same recognition as many of her Harlem Renaissance peers, in part, because the risqué nature of her performances would have kept her out of mainstream venues, newspapers and history books. Today though, Bentley’s story is resurfacing and she is seen as an African-American woman who was ahead of her time for proudly loving other women, wearing men’s clothing and singing bawdy songs.

Years before Gladys Bentley performed in midtown Manhattan, she arrived in Harlem around 1925. After leaving her hometown of Philadelphia as a teenager, she arrived in New York during the Harlem Renaissance and was absorbed into a vibrant artistic and intellectual community.

“The Harlem Renaissance is really a critical point in the history and evolution of African-Americans in the 20th century,” says Dwandalyn Reece, curator of music and performing arts at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. “The creativity that came out of that period shaped music, theater, dance, literature, intellectual thought and scholarship in a way that has shaped who we are today.”

Portraits of Bentley are now held in the music collections of the African American History museum, where the performer is both a face of the Harlem Renaissance and an example of a woman who on her own terms navigated the entertainment business during the Great Depression and Prohibition Eras.

“I think not only of the performative side but that Bentley was a working woman,” says Reece, who described a letter in the collection which shows that Bentley reprimanded a club owner who failed to pay her. “It makes you wonder and ask more questions about what her challenges were in the professional arena and if this was all easy for her,” Reece says.

Despite those challenges Bentley likely encountered in New York’s entertainment business, it is no surprise that she moved to Harlem. As someone who wrote about feeling attracted to women and being comfortable in men’s clothes from an early age, Bentley likely would have found more acceptance in a community that was home to other 𝓈ℯ𝓍ually-fluid entertainers like Bessie Smith and Ethel Waters. Historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. even described the Harlem Renaissance being “surely as gay as it was black”

According to Jim Wilson, author of the book Bulldaggers, Pansies, and Chocolate Babies: Performance, Race, and Sexuality in the Harlem Renaissance, Harlem was also a community that the police turned a blind eye to during the Prohibition Era. People, many of whom were white, seeking entertainment and covert access to alcohol crowded into Harlem nightclubs, speakeasies and parties.

While Harlem was home to African-Americans facing the challenges of the Great Depression, it also became a destination for pleasure-seekers who Wilson says were eager to “let loose of their bourgeois attitudes. . . and experiment both 𝓈ℯ𝓍ually and socially.”

Years before Bentley played midtown nightclubs, she got her musical career started at rent parties, where people in Harlem would cover the costs by charging admission for private parties with alcohol and live performances.

“She quickly made a name for herself as somebody who sang ribald songs,” says Wilson. “She would take popular songs of the day and just put the filthiest lyrics possible. She took the songs ‘Sweet Alice Blue Gown’ and ‘Georgia Brown,’ and combined them and it became a song about anal 𝓈ℯ𝓍.”

Bentley was not the first to sing raunchy music, but Reece said that she was still breaking barriers by “pushing the boundaries of public taste in a way that would have been much more suitable for a man to do.”

After graduating from the rent party circuit, Bentley got her shot at becoming a nightclub performer. In an article she wrote about her life for Ebony magazine, she said that soon after arriving in Harlem she auditioned at the Mad House, a venue on 133rd Street, which was in need of a male pianist.

“At the Mad House, the boss was reluctant to give me a chance,” Bentley wrote. “I finally convinced him. My hands fairly flew over the keys. When I had finished my first number, the burst of applause was terrific.”

In Bentley’s account of her life, her audience was as fascinated by her style as it was by her music.

“For the customers of the club, one of the unique things about my act was the way I dressed,” she wrote. “I wore immaculate full white dress shirts with stiff collars, small bow ties and shirts, oxfords, short Eton jackets and hair cut straight back.”

Gladys Bentley by unidentified photographer, ca. 1940 NMAAHC

Gladys Bentley by unidentified photographer, ca. 1940 NMAAHC

As a singer, Bentley became known for a deep, growling voice and a trumpet-like scat. As a performer, she was advertised by event promoters as a “male impersonator,” and she filled venues with loud, rowdy performances in which she would flirt with women in the audience.

Langston Hughes praised Bentley as “an amazing exhibition of musical energy—a large, dark, masculine lady, whose feet pounded the floor while her fingers pounded the keyboard—a perfect piece of African sculpture, animated by her own rhythm.”

As her star rose, Bentley began playing larger Harlem venues, like the Cotton Club and the iconic gay speakeasy the Clam House. Her act drew white patrons from outside of Harlem, including writer and photographer Carl van Vechten, who based a fictional blues singer in one of his novels off of her, writing that “when she pounds the piano the dawn comes up like thunder.”

Bentley’s fame was a product of being both a gifted singer and an adept provocateur. Her shocking lyrics were accompanied by gossip column stories that readers would have found equally shocking.

“Gladys Bentley had told the gossip columnist that she had just gotten married. The gossip columnist asked, ‘well, who’s the man?’ And she scoffed and said, ‘Man? It’s a woman,’” Wilson says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8b/75/8b752b12-93b7-4aa1-831a-d7fd6a814a3d/2011_57_25_1_001.jpg) Gladys Bentley: America’s Greatest Sepia Player—The Brown Bomber of Sophisticated Songs by an unidentified photographer, 1946-1949 NMAAHC

Gladys Bentley: America’s Greatest Sepia Player—The Brown Bomber of Sophisticated Songs by an unidentified photographer, 1946-1949 NMAAHC

The rumored marriage had all the makings of an early 20th-century scandal—Bentley claimed that not only was it a same-𝓈ℯ𝓍 civil ceremony, but that the union was between herself and a white woman. While Wilson says there is no record of that union taking place, the story is still a glimpse into Bentley’s unapologetic openness about her 𝓈ℯ𝓍ual orientation, and her acute understanding of the power of shock value.

“One of the frustrating and actually joyous things about Gladys Bentley was she was constantly inventing herself,” Wilson says. “Oftentimes when she mentioned something about her personal life, you had to take it with a grain of salt and not necessarily take it for truth.”

By the late 1930s, the Harlem Renaissance and Gladys Bentley, had lost their allure. The Prohibition Era had come to an end, and now white pleasure-seekers frequented Harlem far less than before.

Bentley moved to California, where she continued recording music, touring and performing in upscale supper clubs and bars, but Wilson says her act was a “toned down” version of what it was at the height of her fame in New York.

By the 1950s, Bentley was approaching middle age and the roaring 20s of her youth and the Harlem Renaissance community that flirted with modernism was now a thing of her past.

“The 1950s were even more conservative than the early part of the 20th century. We see a real change so that somebody who is identified as lesbian or gay is considered a national menace. It’s up there with being a communist,” Wilson says. “So Gladys Bentley abandoned that and seems to want to restart her career as a more traditional black woman performer.”

In 1952, Bentley wrote her life story in an article for Ebony magazine, entitled “I Am A Woman Again.” In the article, she described the life of a glamorous performer who silently struggled with herself. “For many years, I lived in a personal hell,” she wrote. “Like a great number of lost souls, I inhabited that half-shadow no man’s land which exists between the boundaries of the two 𝓈ℯ𝓍es.”

After a lifetime of loneliness, she wrote that she had undergone medical treatment that awakened her “womanliness.” She claimed to have married twice, though Wilson says that one of the men denied ever having been married to Bentley. The article was accompanied by photos of Bentley wearing a matronly white housedress and performing the role of homemaker—preparing meals, making the bed for her husband, wearing a dress and flowers in her hair.

Scholars who have studied Bentley’s life said that the story Bentley told about being “cured” in the Ebony article was likely a response to the McCarthy Era and its hostile claims that homo𝓈ℯ𝓍uality and communism were threats to the country. Wilson also says that Bentley, who was aging and no stranger to reinvention, was likely making deft use of the press. “I like to believe that Gladys Bentley had her thumb on the pulse of the time. She knew what was popular, what she could do, and what people would pay to see,” he says.

Her career continued after that point, though briefly. In 1958, Bentley, who grew up in Philadelphia, appeared on Groucho Marx’s game show “You Bet Your Life” where she said she was from Port-au-Spain (her mother happened to be Trinidadian). She took a seat at the piano on the set and performed a song that showed a vocal range and confidence that hadn’t diminished since her days in Harlem.

In 1960, after a lifetime as a popular entertainer and a woman who lived on the fringes in a world that wasn’t ready to accept her, Gladys Bentley succumbed to pneumonia. She had been living in California with her mother and was waiting to be ordained as a minister in the Temple of Love in Christ, Inc. Today, she is being rediscovered for the same reason that her story was obscured during her youth.

“Gladys Bentley should be remembered for being a gender outlaw,” says Wilson. “She was just defiant in who she was, and for gender and 𝓈ℯ𝓍uality studies today, she shows the performance of gender.”