MILLVILLE, N.J. — Mike Trout’s story is riddled with legends of righteous dingers, highlight-reel catches and stuff that made just about everyone question their own eyes.

No, really. Everyone: The townsfolk who know him as simply “Mike.” The scouts who watched him and comped him to other sports legends. Even his own coaches that helped him along the way.

Trout’s 12 years of somewhat quiet dominance in MLB have been on the forefront for all to see. Long before he started his path to major league superstardom, Trout mastered every sport that he’d played: Baseball, basketball, football, ping-pong, golf. It didn’t matter. If there was a stick, a ball or some measure of competition involved, Trout was beating you.

“Let’s just say, worst-case scenario, if baseball didn’t work out, he could play in the NBA,” Arizona Diamondback, friend and fellow Millville citizen Buddy Kennedy told The Sporting News.

MORE: 10 single-season MLB feats we’ll never see again

But on April 7, 2008, deep in the heart of Trout Country, three years before he buttoned up an Angels uniform, the future GOAT penned one of the final chapters in his ascent from scouting question mark to major league superstardom: He threw a seven-inning, 18-strikeout no-hitter.

At least, that’s the way the story was told.

The no-no rests somewhat uncomfortably between myth and reality. If it actually happened, it was one of the single greatest feats of Trout’s youth career, and a highlight of his baseball life.

Despite the game being played in the era of camera phones and YouTube, and despite the no-hitter surfacing in water-cooler conversations and being acknowledged by Trout himself, there’s still an aura around it that fits the performance somewhere alongside Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster.

Maybe the no-no was misreported. Maybe a fat finger hit an “8” instead of a “0” on a laptop. Maybe a game of high-stakes telephone turned a solid Trout outing into a legendary one.

The Sporting News took a trip down the beautiful New Jersey Turnpike to try to filter fact from fiction and get the truth behind the alleged Herculean feat.

As it turns out, the mythical no-hitter is something of a footnote in the story of what Mike Trout means to his hometown — and what his hometown means to him.

‘It’s all about sports here’

You probably won’t believe this, but there are many sides to New Jersey.

Of course, there are the stereotypical ones; there’s the side you’ve seen popularized by MTV, with the orange dudes who extolled the wholesome values of “Gym, Tan, Laundry,” and the ladies who tested the scientific limits of hair products.

There’s the side that you’ve seen in “The Sopranos,” where the cigar-chomping Tony Soprano made the Bada Bing! his base of operations.

There are the booming suburbs, where Thomas Edison stole the idea of the lightbulb invented the lightbulb, just a 40-minute train ride away from New York City.

Then, there’s the side you usually don’t see: The openness and farmlands that make real estate developers drool. The quiet part that plays home to urban legends, like the Jersey devil, and Mike Trout.

Millville, Trout’s hometown somewhat hidden in South Jersey, is the type of backdrop that works as a setting for a Rian Johnson-directed murder mystery. It feels like the majority of the 28,000 are warm and welcoming; They’re eager to point you in the direction of a good restaurant or a place to hang your hat. Cars drive a little slower. Strangers greet you with a “Good morning,” or a “How are you?” Seconds-long exchanges oftentimes turn into 15-minute conversations.

Residents largely know one another on a first-name-last-name basis. Mom-and-pop businesses reign supreme. Everyone eats at the same places. Get it? It’s that kind of town.

It’s also a town that loves its sports and has always celebrated its local athletes, well before the arrival of Trout. Well, the younger one, at least.

“For a long, long time, Millville baseball was Jeff Trout,” Millville baseball coach Kenny Williams told The Sporting News. “Jeff also played football — he was the golden boy in both sports.”

After a promising baseball career was cut short by injuries — his only weakness was his throwing ability, according to his former coach Tony Surace — Jeff walked away from Minor League Baseball, and he and his wife Debbie made Millville home. There were a few reasons for the move: Jeff grew up in Millville, so the familiarity helped. The town had good schools, and Jeff had wanted to pursue teaching. Debbie would also find her way to teaching in Millville.

The last reason that Trout gives, is that Millville is a good sports town.

“The town goes as Millville sports goes. You can feel it when the football team does good, or the baseball team does good,” Thunderbolt Club president Craig Atkinson told TSN.

Atkinson sums it plainly.

“It’s a small town — it’s all about sports here,” he says with a grin.

The school’s “Thunderbolt” nickname was adopted after the P-47 Thunderbolt, the famed warplane used by the U.S. military during World War II. Millville Airport, which resides on the edge of town, used to host training and target practice for the aircraft’s pilots. It’s a slice of Americana that just fits.

Even with Jeff’s minor league history and his son’s destruction of the majors, football was and remains king in the town: The Thunderbolts are coming off a regional championship, and the hunger is apparent. They posted a quarter of a million views over streaming platforms for its 2021 season, despite having a population of under 30,000.

Sports run deep in Millville. The school’s series with Vineland is one of the oldest football rivalries in the country, with the two schools meeting for an 150th time in 2021. The Thunderbolts finished ranked No. 3 in the state in 2021.

“People love Millville football, they just really do,” former Mayor Jim Quinn said. “The easiest sell for me, to sell advertising, is for Millville football.”

Baseball had taken something of a backseat for a long time in Millville. While the little league system was strong, it wasn’t strong enough. If it wasn’t for the ascent of Trout, the area’s craving for baseball wouldn’t be as noteworthy. So says Kenny Williams, one of Trout’s high school baseball coaches.

“It’s not just in Millville, I’d say it’s everywhere within a 50-mile radius of Millville. All the kids want 27 — they want to be Mike,” Williams told TSN.

Surace, a Millville sports icon in his own right, echoed the sentiment.

“Baseball in Millville, South Jersey and New Jersey has all been increased in interest because of Mike. He was the first one to really make it well-known.”

Big fish, small pond? It was something of destiny for Mike to break through the borders of Millville and become something of a sports superhero.

At least, in a way, that’s what his mom believes.

MORE: The untold story of “It’s a Long Way to October,” a groundbreaking baseball documentary

The Trouts met in a way that’s best reserved for a cliche-but-heartwarming romantic comedy. It’s kind of like “Summer Catch,” but with much less Freddie Prinze Jr.

During Jeff’s minor league years with the Double-A Orlando Twins, he noticed a “pretty blonde girl” “gabbin’ away” during a game. His mother urged him to meet her before he hit the road for a road trip to Tennessee, and before she and Jeff’s father made the trek back north to Millville.

“I said, ‘Mom, not now! I’m 0-for-19, I gotta pack, I gotta get on the bus, I got a 12-hour drive with Charlie Manuel and a bunch of drunks,’” Trout said, hoping to avoid the engagement before turning to his father for “backup.”

He found no such reprieve from pops.

“She does have a cute smile, Jeff,” the elder Trout said.

Jeff and Deb would meet, shaking hands in a somewhat “awkward” first meeting. His future wife asked nervously:

“Do you play here every night?”

Jeff describes it as “a baseball story for a baseball family.” He’s got a point, after all, what are the odds that his future wife happened to buy a ticket next to his mom, in a 6,000-seat stadium?

I mean, really. Who writes this stuff?

“You see? Mike was meant to be,” Deb said with a laugh.

‘Unhittable’

There are plenty of (factual) legends of Mike Trout from his youth career. It wasn’t that long ago, after all, so nearly everything is easily verifiable. And yet, there’s the mystery surrounding the events of April 7, 2008.

In a matchup against the Egg Harbor Township, toeing the rubber for the Millville Thunderbolts was No. 1, Mike Trout. It was 2008, Mike’s junior year, and he had quickly become a dominant power pitcher for the Millville staff, in addition to everything else he’d done on the field.

Trout lived mid-to-high 80s and could touch 90, also throwing a disgusting 12-6 curveball that would make Pitching Ninja drool. A traditional power pitcher, he had a tendency of falling behind batters — but he would still strike ’em out.

“If Mike pitched 40 innings, he’d have 80 strikeouts,” Williams said, adding that Trout holds the town’s strikeout record. Williams said Trout was “unhittable” that season.

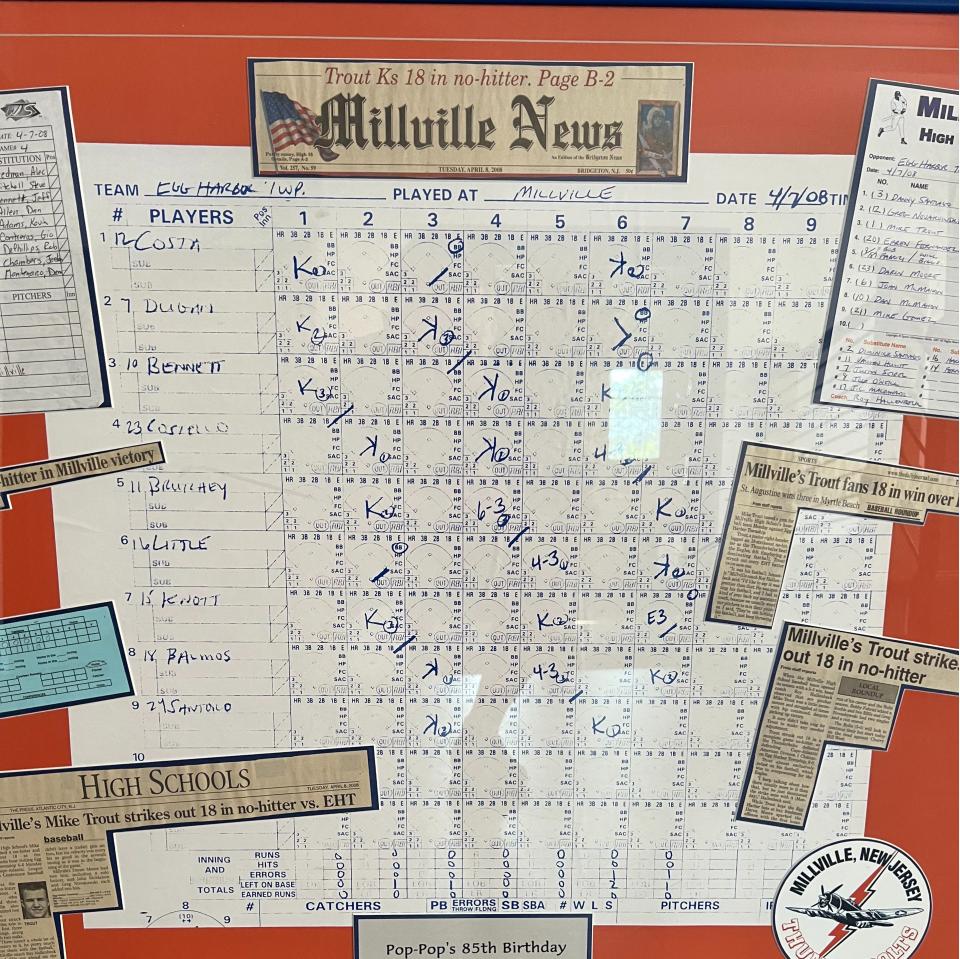

On that day, Trout lived up to “unhittable.” Legend says that Trout struck out an ungodly 18 Egg Harbor batters and allowed no hits. He walked two, and another two batters reached on error in the 6-0 Millville victory. Think about that ridiculousness for a second: Of the 21 outs recorded in the seven-inning game, supposedly, allegedly, 18 came via strikeout.

It should be a simple, open-and-shut case of provable dominance, if not for a small hiccup: When asked about that game, both Millville coach Williams and head baseball coach Roy Hallenbeck, who were both on the bench, were fuzzy on the details.

Despite having seen Trout do amazing things on a baseball field, an 18-strikeout no-hitter seemed a little too amazing.

“Eighteen strikeouts sounds high to me,” Hallenbeck said with a hint of skepticism.

Looking back at the scorebooks, Williams and Hallenbeck couldn’t find that exact game vs. Egg Harbor. But both recalled another dominant Trout outing against Oakcrest High School that same season. They both recalled that Trout threw a five-inning no-no that finished with the application of the mercy rule.

“I thought it was a five-inning, 10-0 mercy rule game, so he only needed 15 outs. But there was some ridiculous, like, 12 or 13 of the 15 outs were strikeouts,” Hallenbeck said.

Williams added: “I don’t think it was 18 strikeouts. I’m pretty sure it was a five-inning no-hitter. Mike just mowed them down — I’m gonna tell you that Mike had 13 or 14 strikeouts.”

While a five-inning no-no with double-digit strikeouts is still impressive, the seeming denial of Trout’s 18-K performance paints the game as more fiction than fact.

It’s still something that Trout could have done — which means there’s more to this than some are remembering.

‘He was a unicorn’

Ping.

Ping.

Ping.

Ping.

Atkinson can still hear the metal clanging of a sound coming from his backyard. When he first heard it, he was confused. He looked out a window to see what it was, and it was a young Mike Trout, hitting rocks over the neighboring fence.

Atkinson, long-time neighbor of the Trout family, saw then that the kid was going to be special. A youth All-Star game confirmed the opinion.

“He plays as a 10-year-old in the 11- and 12-year-old All-Star games, ‘cause he’s that good,” Atkinson recalled, with heavy emphasis on the “that” and “good.”

Drawing out an invisible diagram on a table inside the Thunderbolt Club, Atkinson detailed another of Trout’s somewhat mythical events.

“There’s the left-field fence, then there’s about 50 feet of open space, then there’s woods with trees that are about 80-feet high. He hits a ball that goes over the fence, over the 50 feet and higher than the trees. (Former Mayor) Tim (Shannon) and I, we looked at each other like … ‘Holy s—.’ …

“Mike’s been the best player in every league he’s ever played in, in his life,” Atkinson said. “Why wouldn’t he be the best player in MLB?”

Long before his plaque will be hung in Cooperstown, Trout will have earned his local immortality in the Thunderbolt Club Hall of Fame. As a matter of fact, he already has a fitting stand-in.

In the Thunderbolt Club, an image of Trout at bat, with a list of all his MLB accomplishments, serves as something of a placeholder before his day of enshrinement. And in case there’s any doubt, he’s expected to be a first-ballot Hall of Famer.

The poster of Trout is, hilariously, running out of room to list his accomplishments.

That said, Trout’s dominance of baseball didn’t exactly happen overnight. He wasn’t a surefire star from the second he stepped on a diamond. Instead, it was a consistent ascent from the time he picked up a bat — even though he was better than everyone else he’d ever played against. His youth career is littered with moments when people saw glimmers of greatness.

One of the first such moments came before he hit his eighth 𝐛𝐢𝐫𝐭𝐡day, and it’s something that’s been burned into Jeff and Deb Trout’s memories.

“When he was in tee ball, he was playing shortstop and a bigger kid connected with the ball and hit a line drive up toward the middle, and Mike laid out for it and caught it — as a 7-year-old,” Jeff Trout said. “Deb and I just looked at each other and shook our heads.”

The Trout family has been searching for video of the play, but can’t find it, only adding to the mystique surrounding their son. There was never a singular “a-ha” moment that pointed to Trout’s future greatness, his father said, but that catch was as close to one as it got.

MORE: The inside story of how “This Week in Baseball” got its iconic theme music

During little league games, parents avoided parking their cars beyond the outfield grass on the field — Trout’s developing power would have left dents and destroyed windshields, so parents didn’t risk having to call Safelite. While playing travel ball, other coaches heard stories of Mike, and tried pilfering him for their own squads.

By the time he’d made it to his freshman year of high school, it was clear that he had developing athletic gifts to play at the next level, highlighted by his speed. But in the years that followed, scouts weren’t totally convinced.

“When we were going through the process, the thing we kept hearing was, ‘He was a right-handed position player from the northeast’ — that was one of the knocks on Mike,” Millville baseball coach Ken Williams told TSN. “There was a million knocks on the kid. There are probably a lot of teams that are regretful now, after the fact, that didn’t take him.”

Of course, there are a lot of teams regretful: Trout went No. 25 overall in the 2009 MLB Draft, with the Angels even passing on him with the No. 24 pick, selecting outfielder Randal Grichuk instead.

Players’ projectability at the next level, especially in the northeast, was and remains difficult. Scouts’ jobs are more difficult than they would be in California, Georgia or other warm-area parts of the country where baseball rules; the weather and shorter seasons play a factor into the un-𝓈ℯ𝓍iness of New Jersey prospects. Baseball also faces stiff competition from football participation and other sports in the area, which cuts the player pool a bit, too.

Trout’s pitching prowess was something of a gift and a curse: Scouts who came to see him play and practice would get limited view of him, with the recovery from 80-pitch outings preventing that. He was eventually moved to the outfield, where he stuck.

By the time Mike made it to senior year, the sizzle matched the steak. He was much bigger than his freshman-year frame, and the jump in his game was noticeable. As an added wrinkle in the journey to pro ball, big-name colleges were chasing him down, but he opted to stay loyal to his East Carolina University commitment. That stayed true until his dream of playing pro ball started to become a reality during his senior year.

Thanks to Trout’s Paul Bunyan-esque feats, scouts went from cautious to confused.

“He was a unicorn,” Hallenbeck said. “The scouts did not know what to make of him. I think that’s where some of the intrigue started to grow. He ran like he was much smaller, but he was really big and strong. He was a little bit raw offensively, but because of some of the rawness, he didn’t look like he’d be able to do some things — but then he would do them.

“It’s almost like their numbers weren’t matching up, so they had to keep coming back. They would get a box time down to first base, and it was like, ‘That can’t be right. He’s too big to run that number.’”

Scouts kept coming back to see Trout play, and he would give them something to watch. During a neutral sight tournament during his high school years, Trout hit a ball to left field that dropped jaws — Hallenbeck said scouts were floored by the blast, with some calling it the farthest ball they’ve ever seen a high school player hit.

Hallenbeck also recalled a game vs. rival Vineland, when Trout hit a can-of-corn pop-up to center field that the wind got ahold of. The ball dropped in front of the center fielder, but Trout didn’t just turn it into a hustle double — instead, Trout was “flying” around the bases for an inside-the-park home run.

The scouts were, for lack of a better, more eloquent phrase, shook.

“They all had to get themselves together, because a few of them were recording it. They used their stopwatches to time him around the bases, ‘cause once he popped it up, a lot of them just turned their watch off.”

The scouts who kept coming back tried making sense of what they were seeing. Trout’s combination of size and speed in high school with the pure power earned him plenty of eyeballs, and some very intriguing comps.

“I remember one scout saying, ‘I know this sounds crazy, I only have one comparable for him, and it’s ridiculous to even say it out loud, but the only one I’m coming up with is Bo Jackson,’” Hallenbeck said.

“He said, ‘We have Bo Jackson, and it doesn’t make any sense.’”

The Jackson comp that almost pained the scout to say — and stunned Hallenbeck to hear — wasn’t entirely foolish. Trout’s multi-sport dominance obviously ended up with him on the diamond, but the hardwood and the gridiron were both real possibilities, too, according to all who knew him.

He had played high school basketball, and was named to the All-South Jersey team. Listed at 6-2 — but really, probably at 6-1 — Trout played power forward. His was explosive: He could dunk a basketball with ease, even before hitting 6 feet, and was a tenacious rebounder. He often played with reckless abandon, and terrorized opposing defenses.

“He’s 6-1 and he’s leading the county in rebounds,” Surace said. “You got all these big, tall athletes, and I’m just thinking white guy, he’s 6-1. He averaged 13 rebounds. I thought that was a misprint. Then I watched him play.”

Atkinson added: “There was at least two baseball scouts his senior year at every basketball game. He could have had a college scholarship in basketball.

As a football player, Trout could have been the factory prototype for your 2022 NFL quarterback. He was fast, mobile and had a cannon, all traits that would make for a GM’s dream now. Much to the dismay of his mother, the team wasn’t able to protect him nearly well enough.

That, coupled with other factors, led him to hanging up his shoulder pads after his freshman year in high school.

But, oh, what could have been.

“It was our intention that Mike was gonna be our starting quarterback as a sophomore, and be basically Tim Tebow,” Williams said. “That was the plan. We ran the spread offense back then. Our plan was for him to be that guy.”

Williams encapsulated it after a brief pause.

“Yeah, I know — it’s crazy.”

Trout stuck with baseball, and that turned out to be the right choice. He would hit .531 in his senior year with 18 bombs, the piece de resistance on an immaculate high school career.

“Fast forward again to the springtime (2009) when we started the season, he was kind of like a second- to -fifth-round pick, and in the span of a month, he was a first-round pick,” Williams said, with a caveat:

“Anyone who says he was gonna be the best player in the world isn’t being totally honest with you — I don’t think anybody could have seen that.”

Ultimately, it was decided that Trout would leave the pitching behind after his junior season. His offense, Hallenbeck said, was too important to the team, but more importantly, Mike’s future.

Scouts saw more in Mike than just the production: They saw the intangible stuff. The passion. The drive to win. The kind of stuff that separates the guys who want to make it from the guys who actually do.

“There’s a way about him that, while he’s tormenting you on the ping-pong table or the golf course, he’s very likeable and fun and jovial,” Hallenbeck said. “That whole mix is what made his persona grow a little bit.”

It didn’t matter when, it didn’t matter where, and it didn’t matter which sport: Mike Trout was getting the best of you — even at his own charity golf tournament.

“That son of a b— wins it every year,” Atkinson said with just a hint of sarcastic disdain, pointing at the image of Trout on the wall in the Thunderbolt Club. “He loads his team up, and wants to win every year.”

There have been many ways to describe Trout on the field, course, court or otherwise. He’s coachable. He’s humble. He’s competitive. Hallenbeck put it in perspective.

“He is just a stone-cold 𝓀𝒾𝓁𝓁er.”

‘What are we gonna do?’

Back to April 7, 2008.

Rich Chini was in his second year coaching the Egg Harbor Township Eagles in a matchup against Trout and the Millville Thunderbolts.

Chini pieces together the details of the day, like rewatching a favorite movie after not having seen it for years.

“That lineup wasn’t bad,” Chini said. “It wasn’t bad. …You hear a kid throw a no-hitter, strike out 18 kids, (you think) that it was playing a bad team. It was a state-level, competitive team. We weren’t the best. We were OK — it was a pretty decent team.”

The second thing Chini remembered is that Millville hurler Trout absolutely owned them with an 18-strikeout no-hitter.

“I mean, he was dominant. Nothing else you can say,” Chini said with a laugh. “By the fourth or fifth inning, my assistant coach looks at me and he goes, ‘What are we gonna do?’”

Chini, unfazed, channeled his inner Ric Flair and told his assistant: “If you wanna be the best, you gotta beat the best.”

He wanted the win, because who wouldn’t? Trout tormented them, though: He consistently hit his spots with an assumed plus-90 mph fastball all afternoon. Strikeout after strikeout, Trout was “manhandling” the Eagles, and he was doing it with ease.

“It was like another day at the office,” Chini said.

The game made it to two outs in the seventh inning, with Millville up 6-0. A small slice of baseball history was in the balance, with Trout one out away from tossing a no-hitter.

But you see, the baseball gods have a funny sense of humor, and on this afternoon, they decided to take a trip to Millville.

Egg Harbor center fielder Christian Knott had struggled in the game and during the season, going 0-for-2 in the game with two strikeouts. In his final at bat, he at least made contact, hitting a ball to Millville first baseman Dan McMahon.

That’s when the baseball gods got involved. McMahon lost his balance going after the ball; it glanced off his glove and Knott reached first base. It’s the kind of nightmare scenario that keep scorekeepers awake at night.

Would Trout lose his no-hitter on a 50-50 play like this?

Millville coach Hallenbeck left the dugout and walked over to Chini. Jeff Trout, also in attendance, walked over to speak with Chini, as well.

“Every parent in America would stand up and start yelling, ‘That’s an error! That’s an error!’,” Chini said.

Instead, Hallenbeck and Jeff Trout left the decision in his hands. They both gave him the power to change South Jersey baseball history.

“Coach, you make the call. Is it a hit, or an error?”

‘He’s just Mike’

Every now and then, a hooded figure will walk into Razor’s Edge Barber Shop on North High Street in Millville, get a haircut and walk out without much fanfare. Most know who he is, but no one says as much.

Is it Batman? Pro-wrestling icon The Undertaker?

None of the above. It’s just Mike.

Here’s the thing: Mike Trout isn’t Millville’s favorite son because he’s really good at baseball.

“He’ll pay for a family’s haircut every time he’s in here, and walk out, and they don’t know,” Christian Tipton, longtime friend of Trout’s and owner of Razor’s Edge told TSN. “He’ll say, ‘Make sure they’re taken care of.’ And they’ll have no idea.”

Tipton, who spent plenty of time around the Trout family through the years, saw Trout grow from a “little twerp who always wanted to play” to the much larger, much less twerpy superstar who always wants to play today.

“I think a lot of people forget that he is who he is until they see him live, or they see him on TV,” Tipton said “Because he’s so down to earth. When he’s home — he’s just Mike.”

In 2018, commissioner Rob Manfred made his disappointment known with Trout and his seeming unwillingness to embrace the game’s marketing strategies, to fully take the mantle of the “Face of Baseball.” There was a contradiction there: The game’s preeminent player isn’t a flashy, showy guy, nor has he ever felt the need to be — conversations with those who have known him for his whole life have indicated as much.

After all, this is a guy that still stops by the local Wawa, by his own admission.

What was lost in the discourse, though, is that he’d already become the face of baseball. The on-field successes played into that, but what he does for the town, its athletes and the kids is the truest measure of the Trout Effect.

“I think it gives everybody an inspiration,” Kennedy said. “If he can go out in the world and succeed, everyone else can. He was the one that opened up that doorway that, ‘If he could do it, I can do it.’

“It might not even be in sports, it might be a job or something else in life. But I think everybody had that positive mindset and confidence in themselves to push themselves a little bit past their limits and shoot for the stars.”

He sponsors the Little Angels travel team. Every year, he dedicates his jersey No. 1 to a player who best embodies what he represents on and off the field. The baseball field, now aptly named Mike Trout Field, was renovated thanks to Trout’s urgings to Under Armor.

The Thunderbolt Club, which supports the high school’s athletics by way of scholarships, funding and more, gets a big hand from Mike these days. A lot of that is thanks to the Mike Trout Thunderbolt Club Golf Tournament. Last year, the tourney raised $175,000, with the money going to student athletes. That figure is a massive uptick from the $5,000 or so dollars that the tournament made in years prior.

“We weren’t able to do that (expand scholarships) before Mike,” Atkinson said of the expansion of the club’s finances and endeavors. “Because of Mike and his generosity, we’re able to do a lot more for the student athletes now than we were before.”

Atkinson says that Trout signs whatever he needs whenever he needs it — he puts so much care into signing autographs that he even asks what color Sharpie to use. (Atkinson said black is fine.)

“I understand they want him to be boisterous and loud — that ain’t who he is,” Tipton said. “He’s a good guy, loves playing ball, loves taking care of his family and friends around here. That’s just who he is.”

After all, isn’t that what baseball is about? At some romantic, idealized and admittedly naïve level, it’s about a sport that binds communities. It’s about the adorable Instagram Reels of kids in helmets three sizes too big tripping over themselves while running to home plate. It’s about what makes “America’s Pastime” just that.

It maybe would have been easy for Trout to take his big-money deal from the Angels, build a house in Los Angeles and go full-on “Hollywood” Trout, leaving Millville behind. That, though, was never in the cards.

In the offseason, Trout lives not too far from his hometown, and still visits many of the places he grew up frequenting. From Razor’s Edge to Jim’s Lunch to Verna’s Flight Line Restaurant, he’s still just one of the guys around town. He still has the same group of friends from high school, and in the offseason, they spend time hunting and fishing together.

Surace and Quinn share stories of Millville’s increasingly well-known reputation from around the country. In their travels, strangers know of Millville from Trout’s association with the town. It’s a cool reminder that Millville is more than just a South Jersey town — now, it’s on the map. And it’s largely thanks to a dude who made headlines with his game more than his personality.

Some may find that fact disappointing, while others will find it reassuring: What you see is what you get when it comes to Trout. That’s the consistent message from everyone around Millville; he’s a badass baseball dude and a “stone-cold 𝓀𝒾𝓁𝓁er,” but the three most common words to describe him are “kind,” “generous” and “humble.”

“A lot of people with that power — they would take advantage of that power somehow. He doesn’t,” Tipton adds.

Tipton isn’t the only person who knows Mike as just Mike. Take it from Verna Herman, owner of Verna’s Flight Line Restaurant in Millville. The restaurant is a simple place: Resting just alongside Millville Airport, everyone who eats here knows everyone else.

When asking a waitress whether Trout frequents the place, she answers with an unfazed, “Oh, yeah, all the time” — seemingly not knowing the number of people who would swoon after seeing No. 27 in person, having his favorite breakfast sandwich on an English muffin.

Herman has noticed a difference in the town since Trout’s rise to stardom, but the star himself has remained the same.

“Kids were excited. Everybody wants to be like Mike Trout — everybody,” Herman said. “He really is just a regular, hometown guy. I think he really cares about the area and the people.”

Herman adds that Trout is an excellent tipper, in case you were wondering.

Truth be told, the stories of what Trout has done on the field as a sports superstar somewhat disappointingly overshadow what he’s done for Millville as a down-to-Earth Jersey Guy.

During the worst of the pandemic, all throughout Cumberland County, small gestures of kindness were given to area emergency room nurses and medical professionals, with Trout buying lunches and dinners for overworked staff as they worked to wrangle the pandemic.

Through Millville’s Child Family Center, Trout donated hundreds of gallons of milk and food to needy families during that time, too. Around Thanksgiving, when he’s in town, Trout buys turkeys for families. Random acts of kindness seem to be the standard.

“There were some guys doing some work at my house,” Atkinson said. “One guy says, ‘My dad, who was in his 80s at ShopRite, buying groceries, ready to pay, and the cashier said, ‘Mike Trout took care of this.’ He didn’t even know the guy. Mike went into ShopRite, and for seniors, paid for their groceries around Christmastime.”

Sure, this is a sports story, and there are ultimately — and somewhat coldly — sports ramifications. Millville’s little league system has suffered in recent years, losing one of its two leagues. Football still reigns supreme. But baseball still has a heartbeat, and Trout remains the one for Millville.

“It’s been a huge impact on the kids growing up, I mean, huge,” Tipton said, who has a son in Millville’s little league now. “Everyone’s favorite player is Mike. They all got the Trout shoes, they all wanna be No. 27.”

Ultimately, even with the good deeds, the acts of kindness, the donations, Millville has seen better days. The pandemic took its toll on the town. Businesses along its main roads are shuttered. There are some homeless who make their way up and down the streets with belongings in shopping carts.

The most indicative of what used to be in Millville are the aging warehouses that line the border of the town. The Wheaton Glass factory used to be an institution in town, but all that’s left are the rusted remains, fit for a haunted house or a low-budget horror movie. The town has changed.

Through it all, in the same signature coolness with which he plays baseball, Trout does what he can to help, without the need or want for recognition. He’s a three-time AL MVP, a 10-time All-Star and a $400 million man, but you’d never know it — not because they don’t know him, but because he’s just Mike. Tipton appreciates that about him.

“The second the last game is over in California, the jet is fueled and he’s home. The bags are packed, and he’s home.”

‘It was just his job’

Chini had a decision to make.

On one hand, give a kid on your team a long-overdue hit, even though it ultimately wouldn’t matter, considering he was standing on first base with the E3 or the base knock. On the other hand, Chini wasn’t going to get in the way of a potential star-making performance.

The decision had been made.

“I looked at them and said, ‘This kid is probably pitching one of the best games of his life. It’s an error.”

The game resumed. Then, on the 21st out, Trout struck out Mario Balmos for his 18th of the game. Ballgame over.

(Chini and Egg Harbor would get its revenge on Trout and the Thunderbolts just a few weeks later — but that’s another entertaining story for another time.)

Still, there’s a lot to unpack here: Millville coaches Hallenbeck and Williams both tell of a game that’s not quite what Chini described. Chini’s version is something fit for a Netflix one-off.

So what’s the real story? What’s the myth and what’s the reality?

The proof sits in Mike Trout’s house.

Blown up and framed, is the scorecard from that matchup vs. Egg Harbor. The scorecard tells the whole story — 18 strikeouts. Knott reaching on an error. McMahon at first base. So, yeah. Myth: Confirmed. No need to call the dude with the beret and the mustache.

The frame also has clippings from local papers highlighting Mike’s performance. They all tell the same story:

Mike Trout Fans 18

Millville’s Trout strikes out 18 in no-hitter

At the bottom, there’s a small gold rectangle, with an engraving:

“Pop Pop’s 85th Birthday/April 7, 2008.” So, not only did Mike Trout throw a no-hitter in high school with 18 strikeouts, he did it on his grandpa’s 85th 𝐛𝐢𝐫𝐭𝐡day. It was quite a day.

“(I remember) a sore shoulder after it,” Trout told TSN, half joking. “Nah. It was cool. … I just had everything working that night. I think I was throwing everything: knuckleballs, fastballs, sliders, everything, curveballs. But I definitely don’t miss the pitching days.”

Even more important than Trout’s performance, Chini said, is what came after it.

“After the game, he shook hands with every kid,” he said. “He wasn’t gloating. He said, ‘Good game, coach. Thank you.’ You know how many juniors in high school would be pumping their chest, ripping their jersey off?

“There was nothing to celebrate. It was just his job.”

‘He brings hope’

You probably won’t believe this, but there are many sides to New Jersey. There is, though, only one Millville.

Scattered throughout the town, there are small, barely noticeable signs posted near stop signs and traffic lights, in forested areas by the airport and busier roads.

They read: “Welcome to Millville: Home of Mike Trout.” They’re in the shape of home plate.

If you couldn’t tell by now, Trout would probably have it no other way.

The small signs are the purest, truest measure of the Trout Effect — a humblebrag for a humble guy. It’s the seemingly perfect marriage between hometown and hometown hero.

“I think I need it,” Trout said. “There’s a lot of stuff that comes along with this game. But going back and hanging out with your friends and family, even if it’s just going to get something at a local Wawa or something — it means a lot to me.”

It means a lot to them, too, whether it’s by legend, fact, or Mike just being Mike.

Williams said it best:

“He brings hope to a lot of people.”